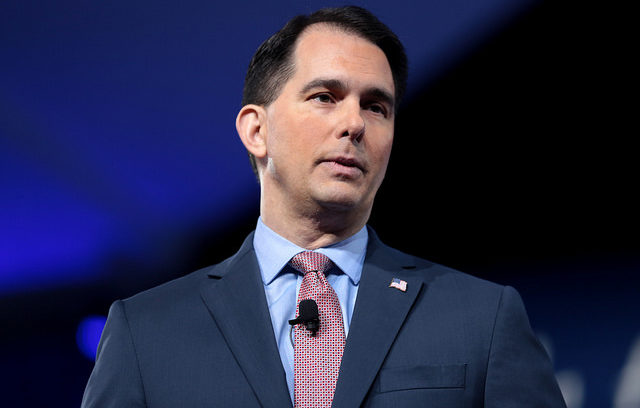

The politics around prisons has shifted since Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker was first elected in 2010.

Now, as Walker seeks a third term (and a fourth election victory), his fellow Republicans have embraced prison reform ahead of the midterms. President Donald Trump has hosted meetings at the White House — and his golf club in New Jersey — about second chances for felons while a majority of GOP voters in Florida support a ballot measure to restore felons’ voting rights.

But Walker has taken a hard line, denouncing a Democratic proposal to reduce the state’s prison population as a plan to let out “violent offenders” as he faces criticism that he has mishandled and ignored an abuse scandal in the state’s correctional system while pushing for privatization.

Walker has been unapologetic about his support for private prisons and responded to Democratic criticism that he had never visited one of the state’s prisons as governor by saying there would be “no value” in doing so.

He also refused to visit juvenile-detention facilities where there were reports of abuse so severe a federal judge ordered the state last year to overhaul operations there.

In 2015, Walker ordered a raid on the facilities — Lincoln Hills School for Boys and Copper Lake School for Girls — to investigate allegations of sexual assault, child neglect and other abuse. But, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported, records showed his administration knew about issues there as early as February 2012 and hadn’t acted.

By 2017, conditions deteriorated, and a federal judge ordered the state to overhaul how it ran Lincoln Hills. According to the Journal Sentinel, a Lincoln Hills teacher who had been attacked by inmates called Walker to discuss safety issues. He refused to speak to her, citing advice from his lawyer.

In May, Walker signed a bill to shut down the facilities by 2021.

As a state representative in the late 1990s, he toured private prisons in Tennessee and Texas housing Wisconsin convicts after he co-sponsored legislation to send inmates out of state.

In 1998, Walker toured a facility in Whiteville, Tenn. — which was run by the Corrections Corporation of America, now one of his political benefactors — where Wisconsin convicts complained they were beaten by guards and tortured with electric shocks.

The guards were also in danger: One was stabbed and taken hostage during a 10-hour standoff and another was beaten a few months later. But Walker was not dismayed and said CCA’s response to the unrest made it more appealing.

“I would think if anything, the way the prison staff responded to the disturbance would suggest we want to continue holding inmates in that facility,” Walker told the Associated Press. “It sounds like they handled it by the book.”

But critics — including former aides — have criticized him for refusing to visit the state’s facilities.

“I repeatedly asked him to come visit the Department of Corrections, visit an institution so he could see what we were dealing with, what the manpower shortage was like,” said Ed Wall, who was the state’s corrections secretary under Walker from 2012 to 2016, in a video posted by Walker’s Democratic opponent, Tony Evers, the state schools superintendent. “I asked him to come to Lincoln Hills specifically because it was such a huge issue in the news that i thought he needed to see what the situation and the circumstances were there. He absolutely refused to go.”

In August, Brian Hagedorn, a state appellate judge who was appointed to the bench by Walker and is now running for a seat on the state Supreme Court, seemed to criticize the governor when he posted on Twitter about his “humbling” visit to see inmates.

In his career, Walker has received at least $10,000 in campaign contributions from the industry — including more than $7,500 from executives at CCA and a $2,500 check in 2016 from GEO Group, a Florida-based prison company — and critics have asked whether his support for policies that would help its bottom line amounted to pay-to-play.

“Often times that’s your greatest challenge, as a legislator, is trying to weed through what everybody’s hidden agenda is, and figure out who’s giving you credible information and in many cases playing one interest off of another to try and figure out what the truth is,” Walker said in a 2002 interview with American Public Media. “More information to me is better.”

But Walker was well aware of who was behind his policies.

As he acknowledged in the interview, the American Legislative Exchange Council provided the model for Wisconsin’s privatization push.

“Clearly ALEC had proposed model legislation,” Walker said. “And probably more important than just the model legislation, [ALEC] had actually put together reports and such that showed the benefits of truth-in-sentencing and showed the successes in other states. And those sorts of statistics were very helpful to us when we pushed it through, when we passed the final legislation.”

At the time, 2,400 lawmakers, most of them Republican, and corporations who paid between $5,000 and $50,000 in dues were members of ALEC. Both Walker and CCA were among them.